Preliminary findings on antenatal, perinatal and postnatal care of refugees in Greece

1 General Information

The information in this report is based on a Survey on Maternity Practices conducted on women living in refugee camps in Greece in the period of September/October 2016. The interviews were collected by a group of volunteers acting on behalf of Pleiades. The questionnaire, prepared by Pleiades and included in Appendix of this document, was defined in context of the international law, excerpts of which are included in section 3.

The number of women who could be reached by the survey is fairly limited due to circumstantial difficulties including, among others, the lack of female translators (desirable if not critical, given the sensitivity of the matter), the lack of professional translators (and resulting potential inaccuracies), and finally the reluctance of women to entrust private information to strangers, often as a result of experienced situations of shame and humiliation.

All information is reported to the best understanding of the surveyors, given in good faith, and collected from trusted sources.

2 Credits and References

This report is the result of teamwork: Electra-Leda Koutra, Ifigeneia Intzipeoglou, Simona Bonardi, Omaira Gill, Milena Zajovic Milka (Are You Syrious?), Dr.Dina Kamba and other volunteers have contributed.

3 Interviews

At 3am my bleeding started. I didn't have emergency contact information. No one did. I had to wait until the camp manager came to the camp the next morning. At 10am the camp manager came to the camp, and my sister-in-law spoke to her. The camp manager said that the ambulance would not come to the camp because it was Saturday. She suggested that I go to the MDM clinic, which is 10 minutes walk from the camp. I was bleeding and she did not offer me a means of transportation at least to reach the clinic, which is 2 minutes away by car. I went to MDM. No gynecologist was there that day. A general doctor visited me and injected a serum. They returned me to the camp after my serum finished. They said "We have no ambulance to take you to the hospital and you should go back to the site where you live and be picked up from there." I was at the office from 2pm until 9pm when the manager left. I was in pain and I was screaming but she didn't care. I left the office and went up the stairs to my tent. My pain got worse. I went to the washroom and miscarried. Ambulance came at 7pm the next day.

[M.S., 35 years old, from Afghanistan, Elliniko airport terminal reception site]

I have such a bad pain in my head sometimes I feel like banging my head against the wall. But the doctors told me it's normal and it will pass.

[Y.S., 19 years old, from Afghanistan, Elliniko hockey stadium reception site]

I had a powder to drink to facilitate going to the bathroom. I stopped having that because I was scared to go to the bathroom at night, when single men were awake and around.

[Z.R., 32 years old, from Afghanistan, Elliniko airport terminal reception site]

The other women at the camp tell me I am foolish to become pregnant. They say "Why did you do this? How will you provide for these children?"

[A.S., 24 years old, from Afghanistan, Elliniko hockey stadium reception site]

After 12 hours of trying to give birth naturally, they told me they will give me a C-section. While I was still awake and bound on the bed they started cleaning the area of my abdomen with alcohol. I was scared and I asked the anesthesiologist for sedation saying in Arabic “Khadirini”. The anesthesiologist started laughing and telling me “no Khadirini”. I panicked and started screaming from the pain and the fear, so much that I tore the belts that kept my hands. Luckily, at that moment, the doctors came in and started talking to me and relaxed me.

[S.O., 37 years old, from Syria, Skaramagas reception site]

I live in a former school class with other 4 families with small children. It is never quiet and I cannot sleep well at night. The situation gets worse considering that I have to sleep on the floor without a mat, which is painful for my pregnant body.

[N.A., 19 years old, from Syria, “Jasmin School” squat in Athens]

3.1 General Remarks

The information in this report is based on a Survey on Refugees’ Perinatal care in Greece which took place in September - October 2016. The Survey, coordinated and conducted by the NGO Hellenic Action for Human Rights - “Pleiades”, will continue and will lead to the publishing of a wider Report.

The Hellenic Action for Human Rights - “Pleiades” is an action-oriented NGO in the field of the protection of Human Rights, having legally publicized its Statute in February 2009, subsequently registered with the National General and National Special records of NGOs in Greece (reg.nr.09110ΑΕΕ12066021Ν-1032), and moreover certified as a structure offering pro bono social care (legal, medical, social, psychological, educational and cultural) by Ministerial Decision (ΦΕΚ 836/τ.Β’/19-3-2012). Its scope is international. The NGO has cooperated with the Council of Europe and several UN’s institutions, as well as with a multitude of national and international NGOs.

Among its activities, the NGO advocates for birthrights, having among others and in cooperation with GHM succeeded in bringing Greece under UN Committee for the Elimination of Discrimination and Violence Against Women’s (CEDAW) 4-year monitoring for the high percentage of CS in the general population. The monitoring ends in March 2017. The report’s preliminary findings confirm that the percentage of CS has not decreased, as regards the perinatal treatment of refugees.

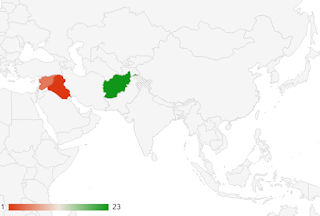

The first part of the survey was conducted in the beginning of October. Twenty-nine women were interviewed in total who live in refugee camps and squats in or around Athens. From them, 23 are from Afghanistan, 5 from Syria and 1 from Iraq. 8 of them are pregnant, 1 had a miscarriage, 20 gave birth and 1 of them lost her child after birth. Their average age is 26 years old. For many of them, this is their first child or have another one to three children.

The most common issues reported are listed in the following table.

Issues reported

|

Inadequate accommodation

|

Lack of safety

|

Lack of sanitation

|

Lack of hygiene

|

Inadequate food

|

Insufficient medical support / services

|

Lack of female doctor personnel or uncertainty about availability

|

Lack of information or inability to access information (denied access or lack of translator)

|

Delayed access to key information (delay of one month or more)

|

Inconsistent information received (assistance and support, access to medical services including exams and child vaccinations)

|

Faced discrimination during gestation or birth

|

Lack of financial means to provide for themselves (food, medicines, necessities)

|

High-risk pregnancy

|

Potentially life-threatening complications (mother or child) resulting from living conditions (including journey to reach Greece) or denied/insufficient assistance

|

Miscarriage resulted from denied assistance

|

No legal assistance

|

Average age of women: 26 years old

Average= 3 Children per woman.

3.1 Pregnancy

All the women interviewed arrived in Greece while pregnant, starting from the spring of 2016 until 10 days ago. Even though they were recognized as such by the authorities upon arrival, they did not receive special care as provided by international, European and Greek law. Instead, they were placed in refugee camps where they faced circumstances entirely incompatible with the condition.

The main problem they report is the low quality of food. As many indicated even though they resided in different camps all around Greece, they could not eat it the food because it was not cooked, stale and dirty. When they found the money, they would always buy food from outside. Also, there was no special provision for extra quantities given their condition. Fresh fruit, vegetables, meat and fish were rarely provided. Thus, all of them report being malnourished during pregnancy, which led to anemia and low blood pressure. Less than half received supplements (vitamins and iron) and the ones who did had to pay for them.

The other big issue was an absence of regular prenatal health monitoring. In their majority, they only visited a doctor once or twice during their pregnancies and some of them did not visit one at all. The routine tests were ultrasounds, blood pressure check and blood check. The doctors always told them that they were fine without further details even if later in their pregnancies they faced serious risks. One woman reports that even though she knew from previous pregnancies that she needs strapping, the doctors told her that she would just need to avoid heavy lifting and refused to perform the operation.

Other concerns were lack of privacy, poor sanitary conditions and lack of gender sensitive policies. The presence of “single” male co-refugees appears to be a threatening factor, particularly during the night, obliging them to avoid circulation even to the toilets.

3.2 Women who gave birth

3.2.1 Babies’ health

The bad nutrition and condition of the mothers affected the children and 6 out of the 20 newborn remained hospitalized in the Intensive Care Unit for more than 10 days after birth. They suffered inter alia from yellow fever, meningitis, lack of vitamin D, neonatal sepsis and tuberculosis, all of which are almost unheard of for Greek children. One of them died. All these diagnoses were not explained to the mothers due to a lack of interpretation.

Many of the women interviewed still did not know what was wrong with their babies at the time of the interview and the interviewers had to translate it for them. For example, the family of the baby that had meningitis found out about it and the fact that they were prescribed a precautionary treatment themselves upon the time of the interview.

Nevertheless, all the babies are being breastfed which led to most of them gaining weight according to the Worlds Health Organisation Health Standards.

Another noteworthy finding is the lack of regular monitoring of the children’s health and vaccination progress. Many mothers were not aware of their babies’ weight in the time of the interview and 3 babies have not been checked by a doctor at all after their exit from the hospital. Some mothers reported that even if there are medical NGOs in the camps they live, they were always unavailable.

As far as vaccinations are concerned, the parents were given vaccination cards in the hospital but it was in Greek and there was no explanation for follow-ups. They could only find the vaccines in NGOs, especially the clinic of Doctors of the World in Omonoia.

3.2.2 Mothers’ health

The mothers totally neglected their health after the birth of their children. None of them monitored her health regularly.

Even though, they were allowed to stay for at least 3-4 days in the hospital, if not more for medical reasons, they were not explained how to take care of themselves during the first 40 days postnatal. The ones that had a CS operation did not return to a hospital for cutting the stitches out because their place of residence was far from the hospitals. As a result, two of them report having open wounds even after a month after their labor which they try to treat by changing their bandages daily.

All the women answered that they would like to received psychological and emotional support from an expert since they feel angry, desperate and anxious. However, no psychologist is available to them.

Their access to family planning and contraception services is also limited.

3.2.3 Place and type of labor

Out of the 20 women, only one did reach the hospital on time for the labor because the ambulance was late. 12 (60%) of them had to have a Caesarian section because of emergency reasons or after trying to give birth for hours. We cannot assess the findings of the doctors because we do not have access to the medical files of the women. However, the women did not feel that they were being bullied into a C-section.

3.2.4 Informed Consent and Refusal

ALL WOMEN (100%) reported that they did not give informed consent during antenatal and intrapartum care. There is no standardized printed information available about options and interventions in pregnancy and childbirth, save for consent forms given in hospital. Women who proceeded to CS (60%) report being asked to sign a document in Greek language, right after the decision for CS was made by the doctors. No woman has been given a copy of that document upon exit from the hospital or at other stage.

In average, there were 4 or 5 doctors and nursing staff in the labor room and some of them were men which was problematic for the women since in their countries gynecologists are only women.

None of the women interviewed by Pleiades (0%) was invited to question any form or decision being made for her. One of them underwent a removal of the uterus after the C-section, without ever being informed about the reason why. Intrapartum interventions were perceived as necessary and not open to discussion. The latter would be impossible in any case, because of lack of interpreter present. Informed refusal and assessment of emotional/psychological coercion by a specialist was out of the question.

In all cases (100%) a labour companion was not allowed, even though all women asked for their husbands to be present in the delivery room. A labour companion is a contentious issue. Acceptance of such a request usually is the case in the general population, in private maternity hospitals. Practices vary. The criteria are not written and known.

3.2.5 Informed Consent and Refusal for Common Birth Interventions

No pain medication was given to women who did not have a CS. Among the women who were subjected to CS, only 1 was given an epidural, while the others were subjected to total anaesthesia. No medical history could be taken before proceeding to anaesthesia, because of complete lack of translation All women who had physiological birth report having asked for pain sedation (through hand gestures), but they got the feeling, from the reaction of the medical staff, that this was not an option in the case of physiological birth.

Augmentation of labour (speeding labour up) – No woman reports being subjected to augmentation of labour. This may be understood by the fact that an ambulance was called on site (refugee camp) upon labour had already started. Women report finding it extremely difficult to convince NGOs operating on camp to call an ambulance for their transfer to the hospital. 100% report finding it extremely difficult to return to the camp or squat, since they had no money and no relative social support. Risks and information about any interventions was never given. No information was given on possible psychosocial support and “medical directions” upon exit from hospital. Lack of interpreters is directly linked to the lack of informed consent. Women have no practical and effective remedy at hand to achieve their information during labour.

3.2.6 Hospital stay

Normally the child was given to the mother immediately for skin to skin contact and breast feeding and stayed in the room with her, unless there were medical reasons for the contrary. In case of problems with lactation, children were provided with artificial milk. However, in one case a child was left with no food for the three first days because the mother was not able to breastfeed it and the doctors refused to give artificial milk.

Clothes were sometimes given during hospital stay. Nappies were always given during hospital stay.

They were not asked for money in the hospital. They did not receive their medical files.

55% (11/20) of the women report a positive hospital stay, where they experienced a good sense of safety and a kind treatment from the hospital staff Nevertheless, this result must be further assessed by interdisciplinary and cross-cultural specialists.

3.3. Postnatal conditions

The problems they face in their place of accommodation after birth remain the same as above since the State once again did not take any action to provide them with better living conditions. Additionally, they report a lack of provision for milk and specialised food for their children that forces them once again to buy it on their own

and a pronounced absence of sanitary environment for them and their kids that puts them in a great risk of infections and contagious diseases.

3.3 Living Conditions

Open fire to warm water for tea in Vasilika camp. Camps do not offer any facility for self-preparation of food.

|

Taps at Vasilika camp

|

In rural areas and open buildings, snakes are common. They are found indoor and outdoor.

|

Crowded tents inside Elliniko airport terminal

Numerous families (including Yazidis) live in camping tents in the area surrounding Elliniko airport terminal. They have occasional, limited or no access to the camp’s services.

|

|

Large UNHCR tents hosting people at Elliniko baseball stadium. Tents are outdoor exposed to the sun all day where temperatures may exceed 40 degrees Centigrade.

|

In Vasilika camp, tents are mounted inside hangars. The problem of rats and cockroaches is common throughout all reception sites. In rural areas and open buildings, snakes are common.

|

Warming water in the sun for use to shower. The solar panels in Vasilika camp in Northern Greece make the hot water too hot for use and there are no controls to regulate the water temperature in the showers. In Elliniko reception sites, hot water is not available.

|

Air ventilation system?

|

Elliniko airport terminal

|

Poor hygienic conditions of bathrooms and occasional flooding

|

In general, there are not enough toilets, showers and water taps in the camps, on average 1 toilet for about 100 people, 1 shower for about 200 people.

|

Throughout camps, promiscuous use of toilets, showers, bathrooms is reported. Women feel generally unsafe to use the facilities at night.

Living spaces divided by blankets and curtains at Elliniko.

|

|

3.4 Food

In most camps three meals are distributed, however the quality is extremely poor. Food is neither varied nor nutritious. Furthermore, cases of expired food and food poisoning were reported over six months in camps throughout Greece.

Pregnant women report being unable to consume the food distributed due to both quality and nausea caused by bad smell.

It is constantly reported that not enough baby food (including milk) is available or distributed. Parents refer to the not-for-profit organization running the medical services also for the provisioning of baby food. Special dietary needs (allergies and food intolerance) are fully neglected.

In many camps/reception sites/shelters, food is reported of poor quality, not nutritious, occasionally old / with mould

|

Self-catering at Elliniko terminal

|

3.5 Access to Medical and Health Services

3.5.1 Children Vaccinations

During the months of July and August, it was announced that vaccinations would be carried out in camps throughout Greece. The following remained unclear: 1) how it could be ensured that all children requiring vaccination be identified/reached (and the procedure for those not reached or unable to attend); 2) the procedure for children missing medical records; 3) the operation was once-off, therefore no sustainable, regular process was put in place for children born after the appointed dates; 4) how to apply for additional vaccinations.

|

4 Law Context

A. Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Dignity of the Human Being with regard to the Application of Biology and Medicine (Convention on Human Rights and Biomedicine)

32. The Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Dignity of the Human Being with regard to the Application of Biology and Medicine was opened for signature on 4 April 1997 and entered into force on 1 December 1999. It has been ratified and entered into force in respect of twenty-nine Council of Europe member States, namely Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Georgia, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Latvia, Lithuania, Moldova, Montenegro, Norway, Portugal, Romania, San Marino, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Switzerland, The former Yugolslav Republic of Macedonia and Turkey.[1] The Russian Federation has not ratified or signed the Convention. Its relevant provisions read as follows:

Article 5: General rule

“An intervention in the health field may only be carried out after the person concerned has given free and informed consent to it. This person shall beforehand be given appropriate information as to the purpose and nature of the intervention as well as on its consequences and risks. The person concerned may freely withdraw consent at any time.”

B. General Recommendation No. 24 adopted by the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW)

33. At its 20th session which took place in 1999 the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women adopted the following opinion and recommendations for action by the States parties to the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (ratified by all Council of Europe member States):

“20. Women have the right to be fully informed, by properly trained personnel, of their options in agreeing to treatment or research, including likely benefits and potential adverse effects of proposed procedures and available alternatives.

22. States parties should also report on measures taken to ensure access to quality health care services, for example, by making them acceptable to women. Acceptable services are those which are delivered in a way that ensures that a woman gives her fully informed consent, respects her dignity, guarantees her confidentiality and is sensitive to her needs and perspectives. States parties should not permit forms of coercion, ... that violate women’s rights to informed consent and dignity.

...

31. States parties should also, in particular:

(e) Require all health services to be consistent with the human rights of women, including the rights to autonomy, privacy, confidentiality, informed consent and choice.”

C. A Declaration on the Promotion of Patients’ Rights in Europe

34. The Declaration was adopted within the framework of the European Consultation on the Rights of Patients, held in Amsterdam on 28-30 March 1994 under the auspices of the World Health Organisation’s Regional Office for Europe (WHO/EURO). The Consultation came at the end of a long preparatory process, during which WHO/EURO encouraged the emerging movement in favor of patients’ rights by, inter alia, carrying out studies and surveys on the development of patients’ rights throughout Europe. In its relevant part the Declaration stated as follows:

“3.9 The informed consent of the patient is needed for participation in clinical teaching.”

D. Article 8 ECHR

“1. Everyone has the right to respect for his private and family life, his home and his correspondence.

2. There shall be no interference by a public authority with the exercise of this right except such as is in accordance with the law and is necessary in a democratic society in the interests of national security, public safety or the economic well-being of the country, for the prevention of disorder or crime, for the protection of health or morals, or for the protection of the rights and freedoms of others.”

Lack of information and consent during the delivery, as is the case with lack of interpretation, constitutes “an interference” with women's Article 8 rights. This interference is not lawful, neither necessary nor proportionate.

The European Court of Human Rights has reiterated that under its Article 8 case-law, the concept of “private life” is a broad term not susceptible to exhaustive definition. It covers, among other things, information relating to one’s personal identity, such as a person’s name, photograph, or physical and moral integrity (see, for example, Von Hannover v. Germany (no. 2) [GC], nos. 40660/08 and 60641/08, § 95, 7 February 2012) and generally extends to the personal information which individuals can legitimately expect to not be exposed to the public without their consent (see Flinkkilä and Others v. Finland, no. 25576/04, § 75, 6 April 2010; Saaristo and Others v. Finland, no. 184/06, § 61, 12 October 2010; and Ageyevy v. Russia, no. 7075/10, § 193, 18 April 2013). It also incorporates the right to respect for both the decisions to become and not to become a parent (see Evans v. the United Kingdom [GC], no. 6339/05, § 71, ECHR 2007‑I) and, more specifically, the right of choosing the circumstances of becoming a parent (see Ternovszky v. Hungary, no. 67545/09, § 22, 14 December 2010).

40. Moreover, Article 8 encompasses the physical integrity of a person, since a person’s body is the most intimate aspect of private life, and medical intervention, even if it is of minor importance, constitutes an interference with this right (see Y.F. v. Turkey, no. 24209/94, § 33, ECHR 2003‑IX, V.C. v. Slovakia, no. 18968/07, §§ 138-142, ECHR 2011; Solomakhin v. Ukraine, no. 24429/03, § 33, 15 March 2012; and I.G. and Others v. Slovakia, no. 15966/04, §§ 135 - 146, 13 November 2012).

Under the Court’s case-law, the expression “in accordance with the law” in Article 8 § 2 requires, among other things, that the measure in question should have some basis in domestic law (see, for example, Aleksandra Dmitriyeva v. Russia, no.9390/05, §§ 104-07, 3 November 2011), but also refers to the quality of the law in question, requiring that it should be accessible to the person concerned and foreseeable as to its effects (see Rotaru v. Romania [GC], no. 28341/95, § 52, ECHR 2000-V). In order for the law to meet the criterion of foreseeability, it must set forth with sufficient precision the conditions in which a measure may be applied, to enable the persons concerned – if need be, with appropriate advice – to regulate their conduct. In the context of medical treatment, the domestic law must provide some protection for the individual against arbitrary interference with his or her rights under Article 8 (see, mutatis mutandis, X v. Finland, no. 34806/04, § 217, ECHR 2012).

The absence of any safeguards against arbitrary interference with patients’ rights in the relevant domestic law at the time constitute a serious shortcoming (Konovalova v. Russia, §45, V.C., cited above, §§ 138-142)

A woman giving birth should have received prior notification about any arrangement interfering with her private life and be able to foresee its exact consequences (Konovalova v. Russia, §46) so as to be capable of making an intelligible informed decision (Konovalova v. Russia, §§ 37, 46).

In order for the requirement of lawfulness of Article 8 § 2 of the Convention to be fulfilled, sufficient procedural safeguards should be in place against arbitrary interference with women’s Article 8 rights in the domestic law and practice, like sufficiency of information provided to the pregnant and birthing woman, in a language that she understands, consideration of refugee women’s vulnerable condition during the procedure, availability of alternative arrangements in case the woman decides to refuse the proposed medical arrangement.

INTERNAL LEGAL FRAMEWORK

In Greece, the relevant matters are regulated by the Code of Medical Ethics (Law. 3418/2005), which replaced the old Medical Ethics Regulation (NW 25.6 / 06.07.1955).

The obligation of the doctor not to carry out medical procedures without the consent of the patient also finds legal basis in the European Convention on Human Rights and Biomedicine (Convention OF Oviedo, 1997) and supplementary in Article 47 of Law. 2071/1992 for hospitalized patients.

The Code of Medical Ethics (L. 3418/2005) reiterated the Oviedo Convention arrangements and worked more closely with the issue of patient consent in its Article 12.

The patient, to which a birthing woman is legally equated when reaching out to a hospital for prenatal and perinatal care, has the right to decide, after receiving adequate information from the doctor, whether to carry out any intervention on her body or health. That right, deriving from the volitional autonomy and self-determination to the body, is constitutionally protected under the free development of the personality and the protection of human dignity (Article 5 paragraph 1 and Art. 2 paragraph 1 of the Greek Constitution).

Apart from its constitutional foundation, the patient's consent plays an important role in civil law.

INFORMATION OF THE BIRTHING WOMAN BY THE DOCTOR

After affirming that the woman has the substantial and legal capacity to consent (i.e. she is not unconscious, or a psychopath, or below 14 years old), the second condition for the validity of the patient's consent to medical practice is her to properly be informed first by the doctor.

In many jurisdictions, the role of informing the patient by the doctor is a necessary element for “valid consent”. A complete and adequate information of the patient enables the latter to freely form their will, having regard to all the parameters and complications involved in the medical practice.

The Code of Medical Ethics rightly states in its Article 12, Paragraph 2, that conditions of validity of the patient's consent is firstly to provide the latter after a full, clear and comprehensible information. In particular, such information, as is clear from Article 11 para. 1 of that Law, includes the content and the results of the proposed medical procedure, consequences and potential risks or complications from execution, the alternatives, and the potential recovery time.

Information of the birthing woman by the physician should be done discreetly, in a non intimidating manner, non forcefully encouraging to consent to medical practice, as health is a particularly sensitive issue, in which the doctor is a dominating figure.

OTHER CONDITIONS

Apart from the above two key conditions of valid consent, the Medical Ethics Code establishes further prerequisites for valid, “illuminated” consent.

Consent may not be conditional or under deadline, and must be be freely withdrawn at any time –although this is not clearly regulated in the Law, it follows from the very concept of consensus as a manifestation of self-determination of the patient and the Oviedo Convention (art. 5 par. 3 and Art . 6 par 5), which is a legally binding text, of hierarchical supremacy.

Furthermore, in accordance with the provisions of RLS and in particular Article 12 para. 2c, we conclude that if the consensus is the result of error, fraud or threat, then it is invalid, without even having to be declared as null. This provision protects the freedom of consent, under the prerequisite that the latter is the product of free will rather than that of coercion or deception.

Under the same provision, the agreement is also void if it is contrary to morality. Such a situation arises when the act to which consensus is asked for, is also illegal or immoral (eg consensus to prohibited killing of the baby), or where the agreement relates to a principle punctuated by an unethical element, such as providing financial “gifts” to stte-appointed doctors. It also holds the view that that medical practice should aim to save an overriding property or benefit expected to be greater than the harm caused by medical practice. Otherwise, the medical practice and the respective consent is illegal.

Finally, Article 12 para. 2 of the Law points out that the consent must relate to the specific medical procedure that is proposed to the patient at that time. It means that consensus relates vaguely to any medical interventions which may possibly take place in the future. To be strong, therefore, consent must completely cover the medical practice and the specific content at the time of its execution. (Art. 12 para. 2d)

The patient's consent before performing a medical procedure is a key issue of the law. The New Code of Medical Ethics was able to enter detailed settings and fill regulatory gaps in the past, mediating in a clear way, among other things, the issue of consent. However, it does not miss defects in its formulation, which hinder its implementation, and omissions, such as the failure to regulate the consensus-making case when the patient is not conscious.

The provisions of this Law are governed by the spirit of respect for human life, dignity and integrity, and human rights in general. Moreover, it, at least theoretically, seeks balance between paternalism, whereby the physician is paramount in the relationship with the patient as a father to his child, and autonomy under which the patient forms its decisions at will.

LEGAL VIEWS ON THE NATURE OF MEDICAL ACTS WITHOUT INFORMED CONSENT - FINDINGS ON GREECE REVEAL A SYSTEMIC PROBLEM

The medical act performed without the valid consent of the patient constitutes "arbitrary medical practice" and violates the principle of medical treatment contract, drawn up between the doctor and the patient. It also runs counter to provision 57 of the Civil Code as an offense to the personality in the manifestation of the person, self-definition and autonomy, in relation to her physical integrity and health.

According to the first view, each medical act is a bodily injury, whether carried out "lege artis" or having had successful results. In particular, it constitutes "harm to the body or health" within the meaning of art. 929 of the Greek Civil Code -any medical act, performed without the informed consent of the patient, is unlawful. Therefore, patient consent is the only reason that removes the illegality of injury (medical intervention). The second view advocates that if a medical act, and especially an operation, such as a Caesarian Section, has taken place without a prior valid “illuminated” patient’s consent, it constitutes an unlawful breach of her personality, under the aspect of the individual's freedom to define oneself, in relation to physical integrity and health.

Irrespective of the nature of the illegality, it is absolutely common place that medical intervention without informed consent is unlawful.

This research reveals that all refugee birthing mothers, without exception, who were subjected to CS, suffered a breach of their right not to be subjected to unlawful medical interventions, and were performed without them being priorly informed and without them providing valid consent. It is also a finding of this research that the lack of interpretation in medical procedures refers to a systemic pathology, based on lack of relevant policies. The systemic nature of the problem and the multi-vulnerability of the subjects – carriers of rights, currently obstruct women in analogous conditions from finding, individually, redress and exit their victim status while giving birth.

5 Appendix – Pleiades Questionnaire

5.1 The interview

1. Where is the interview collected?

2. In which format? E.g. mother is interviewed in person, or the questionnaire is filled in privately by the mother.

3. If in person, was a (female) interpreter used?

4. If by a facilitator/cultural intermediator/other professional (please specify), was a female one used?

5.2 Mother’s information

5. Name/Surname/Asylum Seeker Card No (and Copy)

6. Date of Birth/Age

7. Country of origin

8. Number of children (excluding the pregnancy subject of this interview)

9. Family situation (mother’s marital status, father’s domicile, if pursuing reunification how long since last time husband and wife met, etc.)

10. Vulnerability:

11. Contact number (specify if Whatsapp/Viber available)

5.3 Pregnancy subject of this interview

Section A. Gestation is ongoing at the time of the interview

12. Describe the mother’s health at the time of the interview

13. Are you aware of any health condition affecting you (mother) or the child associated to high-risk pregnancy/birth?

14. Have you received any healthcare advice since learning about your pregnancy?

15. Have you received any medical assistance and/or services (diagnostics, monitoring, check-ups) since learning about your pregnancy?

16. When was the health status of you or your child last assessed?

17. Describe your living conditions during pregnancy:

Section B. The interview is conducted after the birth date

Answer all questions of Section A.

Answer questions 12-17.

Baby’s information

18. Date of Birth

19. Sex

Baby’s health

20. Weight of the baby at the time of birth

21. Weight of the baby at the time of the interview

22. Health of the baby at the time of birth

23. Health of the baby at the time of the interview

24. Was it a premature birth?

25. Were there any birth complications?

26. Were there any post-partum complications?

27. (Refer to following subsections for baby’s vaccinations)

Mother’s health after birth

28. Describe the mother’s health at the time of birth

29. Were there any birth complications?

30. Were there any post-partum complications?

31. Have you received any post-partum healthcare support/medical assistance?

a. Baby’s physical health monitoring

b. Mother’s physical health monitoring

c. Mother’s psychological health support

d. Mother’s emotional support, e.g. under high stress and/or difficult family circumstances

32. Do you have access to community support groups and additional counselling services? E.g. contraception, family support, family planning.

33. Did you have access to breastfeeding education and/or practitioners for professional guidance/advice?

34. Were you referred to any breastfeeding support groups for the duration of the lactation period?

Birth

35. Did you feel safe during birth?

36. Did you or your child face any threats before or after birth?

Living conditions after birth

37. Describe your living conditions after birth:

Ø Go to section B1 if it was “free birth” (mother’s decision to give birth at home or elsewhere without the assistance of a healthcare professional)

Ø Go to section B2 if it was a case of “born before arrival” (mother gave birth at home or elsewhere before the planned arrival of a healthcare professional)

Ø Go to section B3 if birth happened at hospital’s premises

Section B1. Free birth

38. Where did the birth occur?

39. Was it a safe environment?

40. Was it a clean environment?

41. Was a family member or friend with you during labor and/or at the time of birth?

42. If no, was it your choice?

43. Which healthcare professionals were present at the time of birth?

44. Did you have access to clean baby clothes and nappies?

45. Did you have access to pain-relief measures during labor?

46. If yes, were you made aware of benefits and risks?

47. Did you undergo any procedure or treatment that seemed potentially harmful to you or to your child?

48. Are you informed about the compulsory vaccination prophylaxis for your baby?

49. Do you have a vaccination card?

50. Were you able to obtain information and instructions regarding the compulsory vaccinations?

51. Did your baby face any medical condition before or after vaccination? If so, describe what and when.

52. Did you or your baby face life-threatening complications before, during or after birth?

53. Did you seek/receive prompt assistance?

54. Were you or your baby hospitalized after birth?

55. Were you asked to pay money at any stage?

Section B2. Born before arrival

Answer all questions of Section B1.

Answer questions 38-55 of section B1.

56. Summarize events that led to OOH (Out-Of-Hospital) birth. E.g. late arrival of ambulance, hospital too far, etc.

Section B3. Birth at hospital

38. Was an interpreter available in all critical phases, including hospital admission, labor, birth, post-partum procedures?

39. Was a family member or friend with you during labor and/or at the time of birth?

a. If no, was it your choice?

40. Which healthcare professionals were present at the time of birth?

41. Were you allowed to be with your baby after birth?

a. If yes, how long after?

42. Were you allowed to be skin-to-skin with your baby after birth?

43. Was the baby with you the whole time? E.g. Baby bed in mother’s hospital room 24 hours.

44. Did you and your baby have to be separated for medical reasons? If yes, for which reasons and for how long?

45. How long after birth were you allowed to breastfeed?

46. Was your baby given any artificial teats, pacifiers, food, drink without your previous authorization? If yes, were you clearly communicated any medical indication requiring that?

47. Did you have access to clean baby clothes and nappies?

48. Did the personnel conduct themselves in a professional manner? Were they kind? Respectful of your privacy? Did you feel uncomfortable about specific behaviours by the hospital personnel?

49. Were you explained at each stage what was about to happen?

50. Were you normally offered options?

51. Which birth procedure was carried out?

52. Were you offered options regarding the possible birth procedures?

53. Were you recommended a specific birth procedure?

54. If yes, were you explained the reasons?

55. Did you feel that you were being put under pressure or bullied into choosing a specific birth procedure or treatment by any healthcare professionals?

56. Did you feel that you were being put under pressure or bullied into choosing a specific birth procedure or treatment by any family member?

57. Were you allowed to ask questions?

58. Were you provided answers?

a. If not, were there specific reasons? E.g. unavailability of interpreter, unavailability of information, lack of promised follow-up, etc.

59. Were you asked for authorization about the selected birth procedure?

60. Were you offered pain-relief measures during labor?

61. If pain-relief measures were provided, were you asked for authorization before proceeding? Was the procedure explained to you? Were benefits and risks explained to you or to your birth partner?

62. Did you undergo any procedure or treatment that seemed potentially harmful to you or to your child?

a. If yes, did you raise your concerns?

b. If you raised your concerns, was the response adequate? Reassuring? Evidence-based?

c. If no, why?

63. Were you illustrated the vaccination prophylaxis for your baby?

64. Were you provided a vaccination card?

65. Were you given information and instructions regarding the following vaccination appointments?

66. Did you or your baby face life-threatening complications before, during or after birth?

67. Did you receive prompt assistance?

68. Were you and/or your birth partner explained what was happening?

69. Did you or your baby undergo surgery?

70. Were you and/or your partner asked to provide written authorization?

a. If so, was that in a language that you understood?

71. Were you asked to pay money at any stage?

72. Were you granted access to your medical/maternity records?

73. Was your overall hospital experience positive in terms of assistance, support, professionalism?

a. If no, did you make a complaint?

b. Were you offered the option to formalize your complaint?